After 100 years, what is Jack Trice's legacy?

The Iowa State athlete, who died of football injuries, continues to inspire

George Trice unbuttoned his dress shirt and proudly unveiled a skin-deep family tribute.

The ink on his chest shows five bars — a chevron throwback to Iowa State football uniforms from a century ago — and the word “L3GACY7.” That 37 represents the jersey number of Jack Trice, George’s cousin, who died as a result of injuries from a game in 1923.

The story of Jack Trice is a familiar one to many of those connected to Iowa State. He was the first Black athlete to play for the Cyclones. Minnesota players trampled him on the field during play. Trice was transported back to Ames, where he died. An inspiring hand-written letter was found in his suit jacket pocket after his death. The school’s football stadium bears his name after a protracted struggle to honor him.

George Trice, a descendent of Jack, bears his tattoo Thursday at the Parks Library at Iowa State. (Photo by John Naughton.)

George Trice, an Iowa State graduate who lives in Arizona, runs the non-profit Trice Legacy Foundation. He’s been raising funds for causes inspired by Jack, such as providing scholarships and computers to students.

“Do more than your part,” reflecting a line from Jack’s thoughtful letter, written the night before his final game, is his favorite, George said.

This week has been a time to honor Jack Trice, through events on campus and the Iowa State-Texas Christian game Saturday night. A combination of celebration and solemnity. Trice was awarded a degree (he studied animal husbandry) and the Cyclones will wear throwback jerseys.

It’s also time to reflect. After a century since Jack’s death, what is the lasting legacy he has given to us?

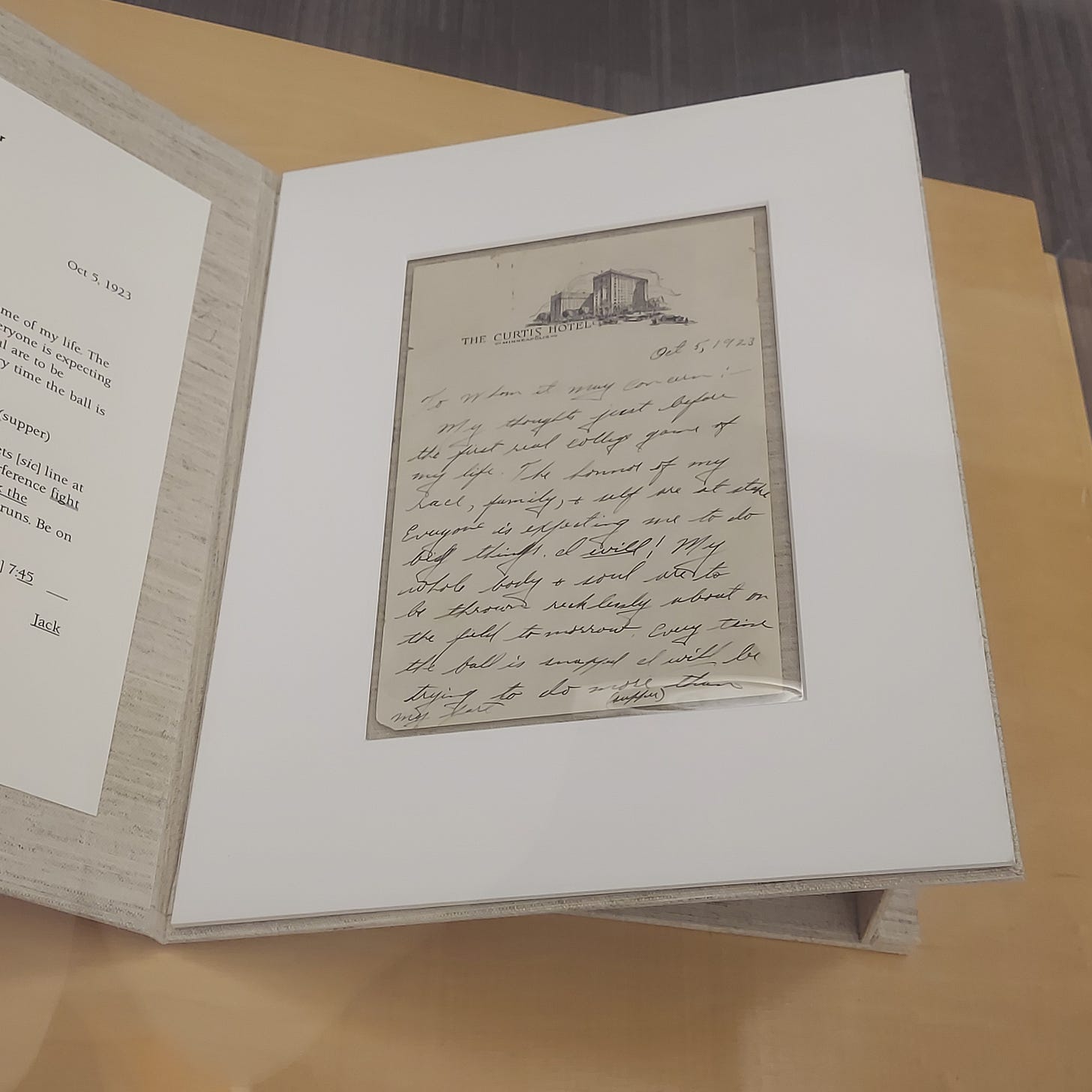

The Trice letter, stored in Iowa State’s Special Collections and University Archives, was displayed at the Parks Library Thursday, then placed back in the vault. It was the letter penned on Curtis Hotel stationary that inspired others and led to the decades-long campaign to name the stadium (“Cyclone Stadium” as its previous moniker). Note: I’ve adjusted the wording to fix typos:

“To Whom It May Concern:

My thoughts just before the first real college game of my life.

The honor of my race, family, and self is at stake. Everyone is expecting me to do big things. I will! My whole body and soul are to be thrown recklessly about on the field tomorrow. Every time the ball is snapped I will be trying to do more than my part.

On all defensive plays, I must break through the opponents’ line and stop the play in their territory. Beware of mass interference, fight low with your eyes open and toward the play. Roll block the interference. Watch out for cross bucks and reverse end runs. Be on your toes every minute if you expect to make good.”

The letter written by Jack Trice the night before the Minnesota game. (Photo by John Naughton.)

If there ever was a “Holy Grail” document of the state’s athletic history, this is it.

The letter was read at a memorial service for Trice a century ago, as it will be this weekend.

“He ended up giving his life,” said Greg Bailey, Iowa State’s director of Special Collections and University Archives.

Trice’s focus was on a football game. He was married and planned to graduate and use his education to help poor Southern sharecroppers succeed. (A mission that Iowa State graduate George Washington Carver pursued in the laboratories of Tuskegee.)

His words were placed on a bronze plaque and placed in State Gym (an ancient athletic building still standing). Mounted in a little-viewed corner, it was rediscovered by a journalism student named Tom Emmerson who wrote an article about Trice for the campus Iowa State Scientist in 1957.

Tom Emmerson, who brought the Jack Trice story to light in 1957, reflected on the history Thursday. (Photo by John Naughton.)

Generations would rediscover the letter and determine that the football stadium would be a fitting place to memorialize and honor Jack and the ideals he demonstrated.

Keep in mind that Iowa’s football stadium was named after a former player, Nile Kinnick. But Kinnick was a war hero (dying in flight training while training as a Navy pilot during World War II) and Heisman Trophy winner. Trice was a relative unknown made immortal by his death. And yet Kinnick’s name still didn’t get put on the stadium until 1972 — nearly 30 years after his death.

A large part of the Iowa State stadium name change fight was carried on by students.

Students graduate.

Eventually, after an awkward transition period when the stadium remained Cyclone Stadium and the playing surface “Jack Trice Field.” Jack Trice Stadium became reality in 1997, becoming the first major college stadium named for a Black player.

An uncomfortable truth, as it were.

“We eventually got what we wanted,” said Emmerson, who eventually became the school’s journalism department chairman.

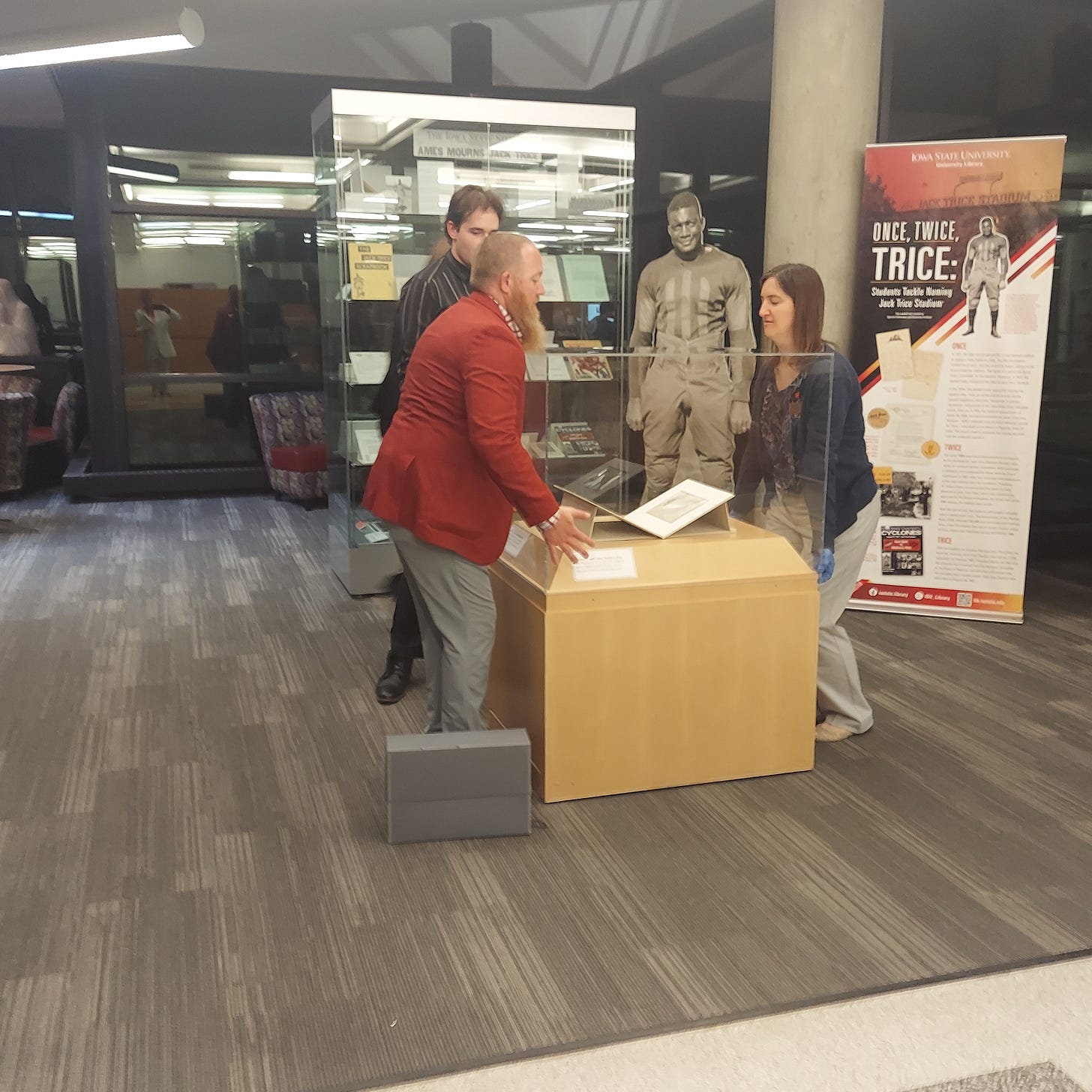

Greg Bailey (left) and coworkers carefully remove the original Jack Trice letter for return to the school’s archives. (Photo by John Naughton.)

So now you know the story. But let’s bring everyone up to speed, and a few more truths that may be uncomfortable.

As much as our better angels would envision a world of Jack Trice-inspired character traits, there are other things to consider, too.

Jack Trice’s image appears on beer. On cereal. His words are marketed and sold (“I WILL” being a popular slogan).

Trice died nearly a century before students pulled in NIL (Name, Image and Likeness). Who should get a cut of the profits being made?

George Trice’s foundation could benefit. The university and athletic department will, too.

A student at a Trice lecture Thursday said the university should offer a class related to his story. Great idea.

As time goes on, the money can benefit a lot of good causes. Rights holders and stake holders can share.

I asked the athletic department for a statement to clarify matters that involve both:

“The university is finalizing a partnership with (the Trice Legacy) foundation for jointly branded merchandise that will generate income for (the) foundation.”

Jack Trice died a century ago. His memory and inspiration survived.

“We’ve come a long way,” George Trice said, “but we’ve got a good way to go.”

Count me as someone with hope. With Iowa State’s leadership, and people like George taking the message and running, there’s a possibility that the true character of Jack Trice will survive for another century.

As I watched library archivists move the Trice letter back to its storage vault Thursday — reminiscent of the “Raiders of the Lost Ark” moment where the Ark is wheeled away — I spoke a contemplative sentence, to those in a century who may continue to be inspired by Jack’s message of determination and pride:

“See you in another 100 years.”

Everyone is expecting big things.

Great article John!!